Cleanliness is next to godliness. At least that’s what people used to say—before Western society at large turned sterile, scientific, and secular. However, in recent years, people are no longer conditioned to associate cleanliness with godliness; even among religious audiences, citing this obscure cleanliness-godliness proverb is unlikely to prompt a change in behavior or even elicit a useful response.

Despite its dwindling familiarity, the motto should not be dismissed without due consideration. Instead, it should solicit a number of questions, such as: What meaning might such a proverb convey? Why did the proverb come to be, and why is it no longer popular? Where did it come from? Who first made this claim? When was the saying introduced, and when does it apply? How are cleanliness and godliness really related? Is there significance, either logical or theological, to this proverb?

From Clean Traditions to Clean Technologies

For religious people familiar with Bible texts, it should not be difficult to recall a few of the many Scriptures pertaining to topics of cleanliness and godliness. Yet despite having an ability to recall particular cleanliness-godliness texts, it is unlikely that people will associate such Scriptures with contexts of physical cleansing in everyday situations. Since New Testament canonization, physical cleanliness has generally not been held as something central to church teachings and traditions. As such, religious institutions typically refrain from using the word clean in religious affairs, especially in physical contexts.

Even though cleanliness appears to be omitted from religious discussions and excluded from the agendas of religious organizations, it is fortunate that Christians remain compelled to uphold certain cleanliness traditions—such as hand washing—apart from their religious institutions. While hand washing appears to be Pharisaic or Jewish in origin (according to New Testament texts), its usefulness cannot be disputed. After all, it has been scientifically proven that cleanliness was an essential aspect of human health and hygiene long before indoor plumbing made hand washing a custom within reach.

Despite the diminishing religious use of the cleanliness-godliness proverb, many modern technologies are dependent on unprecedented levels of cleanliness as mankind pursues omnipotence and omniscience. Far surpassing the cleanliness standards of the medical industry, ‘clean rooms’ of microchip and nanotechnology industries have taken clean to an entirely new level. In these contexts, clean has assumed a new meaning; technology industries can now express clean in terms of microns, nanometers, or even parts per trillion.

Similarly, parents today have taken sanitation exercises to the next level. While years ago, tap water and a bar of soap were once deemed sufficient for the pre-dining hand-cleansing ritual, the use of anti-bacterial soaps, sani-wipes, and even alcohol-based liquid gel sanitizers17 is now the norm. However, it appears that over the course of time, the motivation for cleanliness has transformed from religious duty to scientific enlightenment or even commercial liability.

The Great Debate

Long before microbes were observed under the microscope by the watchful eye of science, Pharisees scrutinized Yeshua’ disciples as they ate their food with unwashed hands. Yeshua defended his disciples’ behavior, despite how irreligious or unorthodox the religious experts of the day perceived it to be. Yeshua even rebuked the religious personalities who blamed and belittled his students for failing to comply with the custom.

Unfortunately, this single exchange between the Pharisees, the disciples, and Yeshua has been used over the course of generations to justify the eradication of physical cleanliness distinctions and principles from the Christian religion. On one hand, the Pharisees seem to be arguing in favor of hand washing and promoting cleanliness-godliness connections; yet on the other hand, Yeshua seems to make claims to the contrary. However, a careful review of the dialogue, in the context of other Scriptures, demands a drastically different interpretation.

While the religious debate between Yeshua and the Jewish Pharisees18 is captured in gospels of Matthew19 and Mark, the Mark account documents the discourse more comprehensively, dedicating almost an entire chapter to the hand washing account. Because the numerous cleanliness, dietary, and spiritual issues cannot be understood without reviewing the full context, the entire gospel of Mark excerpt from the popular New International Version translation is cited below:

The Pharisees and some of the teachers of the Torah who had come from Jerusalem gathered around Yeshua and saw some of his disciples eating food with hands that were “unclean,” that is, unwashed. (The Pharisees and all the Jews do not eat unless they give their hands a ceremonial washing, holding to the tradition of the elders. When they come from the marketplace they do not eat unless they wash. And they observe many other traditions, such as the washing of cups, pitchers and kettles.)

So the Pharisees and teachers of the Torah asked Yeshua, “Why don’t your disciples live according to the tradition of the elders instead of eating their food with unclean hands?”

He replied, “Isaiah was right when he prophesied about you hypocrites; as it is written:

‘These people honor me with their lips,

but their hearts are far from me.

They worship me in vain;

their teachings are but rules taught by men.’

“You have let go of the commands of Elohim and are holding on to the traditions of men.”

And he said to them: “You have a fine way of setting aside the commands of Elohim in order to observe your own traditions! For Moses said, ‘Honor your father and your mother,’ and, ‘Anyone who curses his father or mother must be put to death.’ But you say that if a man says to his father or mother: ‘Whatever help you might otherwise have received from me is Corban’ (that is, a gift devoted to Elohim), then you no longer let him do anything for his father or mother. Thus you nullify the word of Elohim by your tradition that you have handed down. And you do many things like that.”

Again Yeshua called the crowd to him and said, “Listen to me, everyone, and understand this. Nothing outside a man can make him ‘unclean’ by going into him. Rather, it is what comes out of a man that makes him ‘unclean.’”

After he had left the crowd and entered the house, his disciples asked him about this parable. “Are you so dull?” he asked. “Don’t you see that nothing that enters a man from the outside can make him ‘unclean’? For it doesn’t go into his heart but into his stomach, and then out of his body.” (In saying this, Yeshua declared all foods “clean.”)

He went on: “What comes out of a man is what makes him ‘unclean.’ For from within, out of men’s hearts, come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance and folly. All these evils come from inside and make a man ‘unclean.’” (Mark 7:1–23 NIV)

Unfortunately, this text, along with the parallel account of Matthew, is illegitimately and frequently used to seed unkosher and lawless philosophies; both passages have been used to nurture antinomian views of the Bible and to negate numerous teachings of Moses.

The popular conclusion, as seemingly emphasized in the contemporary NIV translation above, is that Yeshua overturned old commandments of Moses, including so-called kosher laws, in favor of greater ‘spiritual’ truths and matters of the heart. But while pondering this text, the reader might be compelled to ask, “What is the meaning of this discourse and teaching?” or “Was this account divinely recorded such that all Old Testament cleanliness and food laws could be negated or dismissed?”

Hard Hearts, Hard of Hearing and Hardly Seeing

In the case of the great debate in the seventh chapter of Mark, Yeshua presented what appeared to be a simple teaching to a varied lot of characters. The text implies the audience was diverse, ranging from self-appointed religious experts to curious onlookers to committed disciples. But after delivering his kosher synopsis, Yeshua departed, probably leaving much of his audience confused and frustrated—to the point where his close disciples asked for clarification.20

Strange as it may seem, Yeshua spoke as he did knowing that his parables would not be understood by many. But this should be expected; Yeshua revealed to his disciples that not all people would comprehend his teachings. He also indicated that the uniform distribution of knowledge and comprehension was not necessarily his goal. But why?

In different gospel accounts of Yeshua’ teaching, the disciples had asked him why he spoke in mysterious parables. Yeshua responded,

The knowledge of the secrets of the kingdom of heaven has been given to you, but not to them. Whoever has will be given more, and he will have an abundance. Whoever does not have, even what he has will be taken from him. (Matt. 13:11–12)

Quoting Isaiah thereafter, Yeshua also explained why revelations were given and received disproportionally.

For this people’s heart has become calloused; they hardly hear with their ears, and they have closed their eyes. (Matt. 13:15)

In other words, a person’s attitude can drastically influence his perception. A hard-hearted man is destined to be hard of hearing as well as virtually and voluntarily blind.

Given Yeshua’ revelations on parable interpretation in Matthew’s gospel, should the reader assume that the great hand washing debate in the seventh chapter of Mark was perceived uniformly among Yeshua’ diverse audience? Surely, since their eyes and ears were opened at differing levels, it stands to reason that Yeshua’ listeners received the message with mixed results. For those looking at Mark’s account with open eyes, several truths might be deduced. For example:

- The principal argument is one of divine authority versus human religious traditions.

- The Pharisees prioritized human washing traditions above Torah given through Moses, thereby encouraging people to usurp or neglect God’s Torah.

- The account addresses human washing and cleanliness; it does not discuss types of animals used for food.

- The Pharisaic tradition implied that a person might be made evil by ingesting “unclean” matter.

In order to fully substantiate these assertions, a more detailed step-by-step study of Mark’s hand washing account has been provided below.

Human Tradition

To underscore the aspects of human religious tradition exposed and discussed in Mark’s account, the text begins by setting the tone with an important contextual backdrop. Logically preceding the Pharisees’ dialogue and Yeshua’ teaching, the account begins by outlining human tradition in the first four verses:

The Pharisees and some of the teachers of the Torah who had come from Jerusalem gathered around Yeshua and saw some of his disciples eating food with hands that were unclean, that is, unwashed. (The Pharisees and all the Jews do not eat unless they give their hands a ceremonial washing, holding to the tradition of the elders. When they come from the marketplace they do not eat unless they wash. And they observe many other traditions, such as the washing of cups, pitchers and kettles.) (Mark 7:1–4)

Beginning with an obvious focus on ceremonial washings, the text introduces the problem and theme of Jewish tradition. This is not to say that all Jewish or human tradition is a problem or unconditionally incorrect, but from these first four verses, the following observations can be made.

- Unwashed hands were assumed to be unclean hands.

- The ceremonial washing of hands and dining utensils was considered to be a tradition of the elders.

- The tradition of the elders governed the behavior of Pharisees and Jews before meals and following marketplace visits.

- The tradition of the elders was evidently well established; such practices were familiar in Israel, probably for generations.

- The scope of the traditions of the elders included cleansing of dining implements.

Seeing this information from the first four verses in the proper light is pivotal, since they introduce the central theme of the entire text, and because Yeshua’ statements are without pertinence if this preamble is not fully understood. After reviewing these first four verses, however, many conclude with closed eyes that the “tradition of the elders” defined cleanliness practices verbatim according to Moses’ Old Testament stipulations. However, verses to follow demonstrate the fallacy of such interpretation; Moses’ commandments on cleansing and cleanliness are not identical to the practices or “tradition of the elders” as described above.

Continuing Contrasts—Moses versus the Elders

Continuing with Mark’s account, the vivid contrast between the religious tradition and the commands of Elohim is succinctly and repeatedly underscored. As in the majority of Yeshua’ rebukes recorded in the gospel accounts, the basis for argument and dialogue is provided by the Pharisees, who introduce two topics of debate with a single morally loaded question. The account continues,

So the Pharisees and teachers of the Torah asked Yeshua, ‘Why don’t your disciples live according to the tradition of the elders instead of eating their food with unclean hands?’ He replied, ‘Isaiah was right when he prophesied about you hypocrites; as it is written: ‘These people honor me with their lips, but their hearts are far from me. They worship me in vain; their teachings are but rules taught by men.’ (Mark 7:5–7)

From the religious authorities’ own inquiry, it is obvious that they were more concerned about the “tradition of the elders” than they were with Mosaic Torah. Erring on the side of caution, the religious authorities had presumed the disciples’ hands to be unclean; yet circumstance or evidence testifying to the disciples’ uncleanness is absent from the text. Furthermore, Yeshua’ citation of Isaiah would suggest that the Pharisees’ ancient washing traditions were of human origin; as far as true Old Testament commandments were concerned, such traditions were extrapolated at best,21 and in some cases, altogether impostors. After all, according to Leviticus, eating restrictions were not imposed on “unclean” people apart from festive gatherings,22 nor had the Torah stipulated cleansing activities of any sort (e.g., hand washing) prior to the intake of food.

As if quotation of Isaiah’s prophecy was inadequate, Yeshua again accused the Pharisees, explaining their error to them in his own words. Contrasting God’s Torah with man’s Torah a second time, he rebuked them, saying,

You have let go of the commands of Elohim and are holding on to the traditions of men. (Mark 7:8)

This statement begs two questions: what are the commandments of Elohim and what are the traditions of men? Sadly, many traditional Christian institutions teach congregants to pair one idea with the other; they infer “traditions of men” to mean “laws of Moses.” But Yeshua never suggested that Mosaic Torah was to be demoted to that of human invention or pointless ritual; he taught the opposite.23

Repetitious Human Traditions

As if the first accusations were insufficient in contrasting Mosaic Torah with human tradition, Yeshua provided yet another example, comparing the Pharisees’ behavior against Moses’ ideals. Rebuking them, Yeshua said,

You have a fine way of setting aside the commands of Elohim in order to observe your own traditions! For Moses said, “Honor your father and your mother,” and, “Anyone who curses his father or mother must be put to death.” But you say that if a man says to his father or mother: “Whatever help you might otherwise have received from me is Corban” (that is, a gift devoted to Elohim), then you no longer let him do anything for his father or mother. Thus you nullify the word of Elohim by your tradition that you have handed down. And you do many things like that. (Mark 7:9–13)

Since he denounced the religious leaders three times for preferring human traditions over commandments of Elohim declared by Moses, it is no surprise that Yeshua would leave the crowd with an accurate account of God’s directives pertaining to uncleanness. Again, speaking deliberately and in accordance with Leviticus, Yeshua reminded the audience,

Listen to me, everyone, and understand this. Nothing outside a man can make him unclean by going into him. Rather, it is what comes out of a man that makes him unclean. (Mark 7:14–15)

Even though Yeshua’ earlier statements set clear precedent, as he repeatedly advocates Moses’ Torah above human tradition, the two verses above are nevertheless inferred to teach the very opposite. According to dispensational theologians, these verses are interpreted as Yeshua’ vocal opposition to Moses’ Torah. But closer examination of the Old Testament Scriptures does not support such this view. In fact, if Yeshua’ public proclamation is compared with Moses’ writings, it becomes evident that Yeshua’ public teaching was not limited to eating; rather it was a summary of more than a chapter of the book of Leviticus24 dedicated to hygienic commandments, distilled into just two concise sentences. Yeshua was not debunking Moses’ cleansing principles; instead, he was succinctly reiterating them.

Unclean Sources—Out and On versus In

It is reasonable to deduce from Yeshua’ words of hygienic wisdom and the Mark 7 introduction that the Pharisees attempted to err on the safe side—even adopting a cleansing philosophy and traditions that were beyond Moses’ prescriptions. From Mark 7, it would appear the Pharisees believed that anything unwashed should be regarded as unclean. Likewise, the gospel reader might be vulnerable to making a similar correlation, but only if not familiar with Moses’ teachings. After all, Moses never indicated that a person could become unclean by what he ate. To the contrary, Moses indicated that a person could become unclean by that which he touched, and more specifically, by that which his body exuded. In other words, Moses taught that personal uncleanness was contingent on what came out of him, or what came on to him, but not by what was put in to him.

As alluded to in Yeshua’ concluding statement,25 personal uncleanness could indeed result from a variety of human bodily discharges. According to Leviticus, discharges such as blood, saliva, phlegm, feces, puss, or semen could render the person with the discharge “unclean,” as could rashes or skin disease.26 Needless to say, all of these bodily fluids are capable of making people unclean, and they would also be regarded as things “coming out of a man,” just as Yeshua frankly described.

In addition to discharges from the human body, Leviticus also indicates that certain animal varieties were capable of making people unclean. Referring to “unclean” animal varieties, Moses’ Torah explains,

If a person touches anything ceremonially unclean—whether the carcasses of unclean wild animals or of unclean livestock or of unclean creatures that move along the ground—even though he is unaware of it, he has become unclean and is guilty. (Lev. 5:2)

Note that Moses is not referring to eating as the means by which a person became unclean; instead, he is referring to mere physical and external contact with the carcass. In other words, Moses is referring to a case of on and not in, even though the very same animal carcasses that were forbidden to eat were also forbidden to touch.

Furthermore, Moses’ Torah included similar provisions for inanimate objects such as utensils and clothing. With similar sanitary concerns, Moses gave instructions relative to unclean animal corpses,

When one of them dies and falls on something, that article, whatever its use, will be unclean, whether it is made of wood, cloth, hide or sackcloth. Put it in water; it will be unclean till evening, and then it will be clean. (Lev. 11:32)

In all probability, the Pharisaic elders’ washing traditions—as applied to hands and utensils—were extrapolated from such commands. However, these Pharisaic directives failed to meet the letter—or the spirit—of Moses’ Torah.

A Crash Course in Levitical Washings

After carefully scrutinizing the washing expectations recorded in Moses’ writings, it becomes obvious that people and things subjected to unclean substances would not necessarily attain a status of “clean” if cleansed under the alternate set of washing traditions as introduced by Israel’s elders. For example, earthen vessels made of porous clay were not to be treated via ceremonial rinsing if exposed to uncleanness; they were to be destroyed instead.27 Depending on material of construction, certain objects that were exposed to unclean things were not to be merely rinsed with water; some were to be purified or sterilized by fire. 28 Furthermore, it appears that the elders’ tradition as described in Mark 7 failed to incorporate time delays as Moses’ cleansing directives required.

As for unclean persons, if there was any washing to be done, it was to be done as stipulated by Moses’ Torah. Contrary to the elders’ limited hand washing traditions as described in Mark 7, Moses’ Torah instructed,

Whoever touches the man who has a discharge must wash his clothes and bathe with water, and he will be unclean till evening. (Lev. 15:7)

However obscure or arbitrary the contemporary Gentile Christian may perceive this Mosaic Torah to be, it is essential to note how Mark’s account presents the Pharisees’ hand washing effort as superficial in terms of compliance with the Leviticus text.29 In addition to failing to wait the prescribed time to declare an object or person clean, the Pharisaic tradition also failed to honor the full body wash expectation as established in Moses’ writings.

Ironically, according to Leviticus, hand washing was required to be performed by the unclean person with the bodily discharge. Referring to unclean persons, Moses wrote,

Anyone the man with a discharge touches without rinsing his hands with water must wash his clothes and bathe with water, and he will be unclean till evening. (Lev. 15:11)

In a sense, by washing their own hands, the Pharisees were acting as if they themselves were the unclean persons, who would be technically unfit to attend public dining assemblies without a full body wash. To add to the irony, they were calling the disciples unclean without having a basis for doing so. The Pharisees did not honor the fact that not everything washed per their tradition was clean according to Moses, nor did they seem to accept the possibility that something could be clean even though it was not washed.30 Instead, they zealously presumed every person, place, and thing was dirty;31 they meticulously washed only implements and extremities as a precaution; and they incorrectly surmised that their washing rituals immediately cleaned everything. However, contrary to the elders’ expectations, Moses did nothing to prohibit an unclean man from eating or from handling his own food while he was in an unclean state.

Unclean and Evil Origins

Through manmade religious washing rituals, the Pharisaic sects had deceived the people into believing they might be made unclean as a result of incidental ingestion of minuscule unclean or defiled matter—as if it might permeate the stomach and overcome the spirit or ‘heart’ of a man, compromising his moral fortitude. The people came to mistake the elders’ rituals for Moses’ mandates. They accepted Pharisaic paranoia in place of Moses’ prudence. Thus, Yeshua was compelled to reiterate Moses’ teachings relative to the topic of cleanliness, setting the record straight before the Pharisees.

However, Yeshua did not elaborate on the moral implications of his two-sentence synopsis of Leviticus until he withdrew from the crowd, and until after his disciples inquired of him. Mark also records this private inquiry, in which the spiritual aspects of the Pharisees’ doctrinal error become more obvious.

After he had left the crowd and entered the house, his disciples asked him about this parable. “Are you so dull?” he asked. “Don’t you see that nothing that enters a man from the outside can make him ‘unclean’? For it doesn’t go into his heart but into his stomach, and then out of his body.” (In saying this, Yeshua declared all foods “clean.”)

He went on: “What comes out of a man is what makes him ‘unclean.’ For from within, out of men’s hearts, come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance and folly. All these evils come from inside and make a man ‘unclean.’” (Mark 7:17–23)

Unfortunately, in interpreting these isolated gospel texts without Moses’ Torah, many people infer Yeshua’ private remarks to be outright permission to ignore the physical mandates in favor of the spiritual revelation, not taking into account the illegitimate Pharisaic cause-effect theology that Yeshua was dispelling.

Yeshua had to clarify to his disciples that evil or immoral behavior was not the consequence of eating dirty food. It stands to reason that Yeshua did not make this statement in a vacuum. To the contrary, he had to underscore where evil came from because the traditions and teachings of the religious authorities were so pervasive, confounding, and effective in distorting the truth pertaining to the origin of evil. From the account, there is every reason to believe that Pharisaic behavior had led the disciples—and the masses—to believe that evil or evil inclinations could manifest within people because of something they ingested orally. They took the old “you are what you eat” adage a step too far, inferring that a person who ate evil would become evil!

If not for the prevailing perceptions on the external origin of evil inclinations, Yeshua’ closing comments in Mark 7 must be viewed as an abrupt change of subject and a topic out of context, especially if Levitical teachings are not considered. However, in acknowledging the simple truth of Leviticus in its entirety—namely, “that what comes out of a man makes him unclean”—Yeshua’ private revelations following the debate must be interpreted as supplementary information, as opposed to statements overturning or correcting previous Mosaic instructions. To reiterate, Yeshua never challenged relationships between physical illness and unclean animal varieties used for food; instead, he underscored the disconnect between physically dirty hands and moral depravity. As such, Yeshua’ teachings were a far cry from declaring all foods to be “clean.”

Liberal Interpretation of Literal Writing

Nevertheless, out of unfamiliarity with—or possibly in contempt of—Moses’ Torah, some take Yeshua’ concluding remarks to illogical extremes, distorting his words to negate not only elementary hygiene laws, but extending even greater distortions to the dietary laws. Many English Bible translations liberally state outright that “Yeshua declared all foods clean.” However, in examining many older English translations, 32 it becomes apparent that most texts exclude the misleading parenthetical statement from verse 19 (“Yeshua declared all foods clean”). For example, the Shakespearean King James Version interprets the text,

“And he saith unto them, Are ye so without understanding also? Do ye not perceive, that whatsoever thing from without entereth into the man, it cannot defile him; because it entereth not into his heart, but into the belly, and goeth out into the draught, purging all meats? And he said, That which cometh out of the man, that defileth the man.” (Mark 7:18–20 KJV)

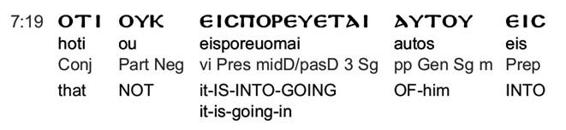

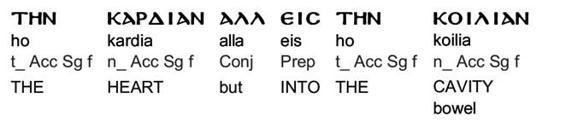

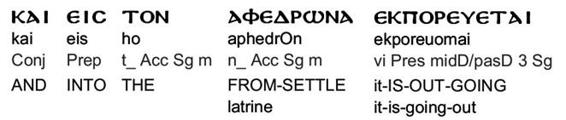

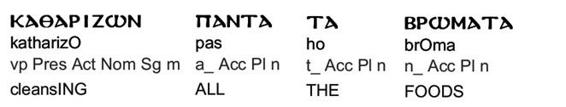

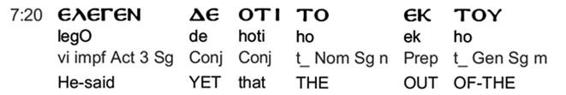

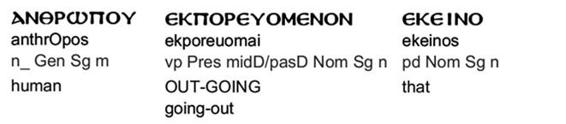

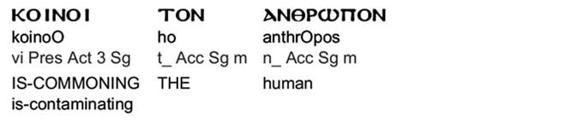

In comparing this old English with more contemporary translations, as demonstrated on the prior page, it becomes apparent that Yeshua’ parenthetical food cleansing claim is completely absent from the King James text. Likewise, a word-for-word interlinear translation33 is more consistent with the King James text, leaving a gaping hole where the New International Version adds the ambitious claim that Yeshua “declared all foods clean.” To illustrate this, the Greek-English interlinear translation34 of Mark 7:19-20 is provided below.

(Mark 7:19–20 ISA)

From the Greek text above, it is clear that the original language fails to support the parenthetical “Yeshua declared all foods clean” statement. However, if the text is rendered without superfluous interjection, Yeshua’ teaching is better understood and is not twisted to mislead the reader. The Greek text describes the passage of food through the body, where food goes from field to hand to market to hand to mouth to stomach to latrine, with stomach acid and the bowels processing whatever a person might have ingested accidentally. It is credible to reason that Yeshua described the digestive process as one of cleansing, the stomach acid compensating for minor contaminants that a person might ingest due to contact with unwashed hands. But the digestive process would not leave the matter “clean” in the latrine in the end, as human defecation (regardless of preceding diet or preparation of food) is cited as uncleanness by Moses and the prophet Ezekiel alike.35 Instead, the bowels were what was being “cleansed” or “purged” or “flushed.” Thus, Yeshua’ point in the gospel of Mark was simple: whatever you eat will be expelled from the body, and nothing evil will rub off on you on the inside as it passes through your system!

Common English and Unclean Greek

Adding to the confusion, words resembling “unclean” are not translated consistently in English Bible translations. In fact, “unclean” and other words including “defile,” “defiled,” “foul,” “polluted,” “unholy,” and “common” are used somewhat interchangeably in the place of three different Greek words, which also carry unique and distinct connotations.

For example, the Greek word in Mark chapter 7 describing the disciples’ unwashed hands (κοινός/koinos)36 is an adjective that might be most universally translated as “common” or “shared,” as it can always be related to public or community contexts.37 Yet even though κοινός/koinos occurs in New Testament texts outside of cleanliness or moral contexts,38 the translators—much like the Pharisees—nevertheless opted to interpret the terms with negative connotations in particular places, using words like “defiled” or “unclean” to describe the disciples’ hands. As suggested previously, the actual state of the disciples’ hands prior to their encounter with the Pharisees is uncertain. Therefore, it stands to reason that, where used biblically in various New Testament contexts, the English adjective “unclean” would be better understood as something “un-clean;” that is, something of uncertain purity or cleanliness, as opposed to something that is positively identified to be dirty or defiled. For such reasons, a more accurate and morally neutral term, such as “common,” should be considered for all New Testament occurrences of κοινός/koinos, lest the reader be coaxed into drawing presumptive conclusions.

Moreover, it is of note that the adjective κοινός/koinos is only attributed to objects, and that these “common” or “shared” objects are not credited with the unconditional ability to “defile” or “make unclean,” as translators also suggest when interpreting the Greek verb κοινόω/koinoō39. In further emphasizing communal connotations and links between κοινός/koinos and κοινόω/koinoō, it becomes evident that Yeshua’ use of the verb κοινόω/koinoō in the Mark 7 account has more to do with “making common” and less to do with corrupting or polluting. Of course, by implication, the verb κοινόω/koinoō strongly implies to “make unholy,” as the term “holy” refers to something that is “set apart,” which is the very opposite of something that is “common,” “shared,” or “public.” Therefore, it would be appropriate to suggest that Yeshua said that nothing “common” (κοινός/koinos) is capable of “commoning” (κοινόω/koinoō), i.e., making people “common” or “unholy.” Thus, the New Testament indicates that people are not to be described as common (κοινός/koinos), 40 and that people could not be made unholy (κοινόω/koinoō) spiritually from encountering something that is common.

The Mark 7 account, however, makes no reference to the Greek adjectives that may be used to describe food of an unclean variety, such as meat derived from the types of animals that Moses forbade to eat. Derived from a different word, the adjective ακαθαρτος (akathartos, which is an antonym for clean)41 is used to describe evil spirits and animals of an unredeemable variety—having the power to corrupt—which Yeshua never cleansed. Although Yeshua cleansed people of spirits and ailments which were ακαθαρτος (akathartos) by nature, he never cleansed animals or foods that were ακαθαρτος (akathartos). Things such as mold, parasites, or evil spirits would be described as ακαθαρτος (akathartos), in the same way that the Bible describes unclean animals such as pigs, shellfish and cockroaches. Essentially, the Pharisees of Mark 7 ascribed the same attributes of unclean things, which are ακαθαρτος (akathartos), to all things common (κοινός/koinos).

Spiritually Unclean Food and Proper Repentance

While Yeshua did say that ingesting mishandled or “common” things would not render a man evil, it is of critical importance to reiterate that the surrounding or parallel accounts make no mention of various animal/food types and their Old Testament distinctions. Making a theological commitment to dispensational dogma, common English and unclean Greek interpretations, or superfluous translations will ultimately pervert, not to mention invert, the gospel message. Instead of promising forgiveness in response to repentance, the substitute gospel becomes, “Yeshua died—Moses’ dietary and cleanliness laws need not apply!”

This message of lawlessness is the polar opposite of the true gospel, particularly as it appears in conjunction with some of Yeshua’ earliest recorded teachings. For example, according to Matthew, the mandate of repentance is inseparable from the gospel or “good news” idea.

After John was put in prison, Yeshua went into Galilee, proclaiming the good news of Elohim. ‘The time has come,’ he said. ‘The kingdom of Elohim is near. Repent and believe the good news!’ (Matt. 11:25–26).

Whether in English, Hebrew, or Greek, the words for repent42 carry connotations beyond regret; they always imply change and return. But without a standard whereby morality is determined, the idea of repentance is almost pointless—it is speculative at best. True repentance requires an affirmative standard by which to define good deeds, just as it requires a prohibitive standard or commandments in order to define deviant behavior.

Thus, repentance without Moses’ standards for reference is folly; it is arbitrary and baseless. The same repentance-gospel relationship was conveyed by John the Baptist before he was imprisoned.43 It defies logic to propose that John and Yeshua were attempting to preach a new form of repentance or to convince the children of Israel to ‘return’ to a new gospel. While theologians imply that the gospel message is limited to teachings in the era of Yeshua’ incarnation, every book of the Bible points to the fact that the gospel is timeless: there is no time like the present to repent from evil and be restored to the Creator.

Mark’s Message

Despite the way those claiming to represent Christian institutions and doctrines may try to represent the teachings of Yeshua, a simple truth cannot be overstated: Yeshua never made any attempt to redefine either food44 or cleanliness as stipulated by Moses. He did not compel his disciples to adopt behaviors contrary to those of Moses, as did the Pharisees of the gospel accounts. Regardless of calendar date, BC or AD, God’s Word conveyed through Moses, along with the definition of repentance, remains unchanged. To paraphrase Mark, Matthew, Moses, and Yeshua, what comes out of people can make them unclean, but eating common or dirty food won’t make people evil!